A $36.3 million renovation and expansion of the Jones Library will proceed after voters at Tuesday’s biennial election overwhelmingly affirmed the Town Council’s April decision in favor of the project.

Tag: Library Construction

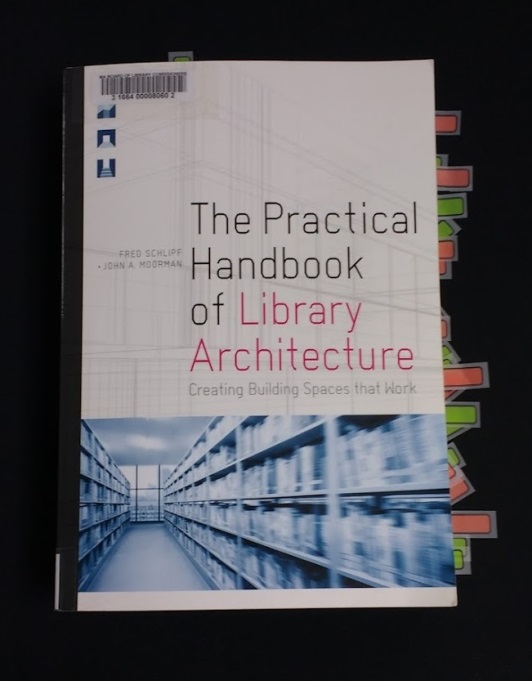

A Must Read for Library Construction

By MBLC Library Building Specialist Lauren Stara

Every once in a while, a book comes along that is packed with so much good information that you want to share it with everyone. In this case, that means everyone who is planning a library construction project.

The Practical Handbook of Library Architecture: Creating Building Spaces that Work by Fred Schlipf and John A Moorman (ALA, 2018) is the book.

To be honest, it’s a little intimidating at nearly 1,000 pages, but don’t let that stop you. The authors are librarians who have decades of experience with library design and construction from the librarian’s point of view, and they’ve put it all down in black and white with humor and style. Chapter Two is entitled “More than Two Hundred Snappy Rules for Good and Evil in Library Architecture” – need I say more?

Topics run the gamut from the 10,000 foot view (overviews of the design and construction processes) to the granular (the wording for the plaque that goes in the lobby), and everything in between. There’s even a chapter called “Evaluating Library Buildings by Walking Around” that’s great for assessing an existing facility. You can see from the photo that I started flagging important passages, but after a few chapters I had to stop because I was running out of flags.

This is a book that former MBLC Construction Specialist Patience Jackson could have written, for those of you who know her. It’s the book I wish I had written, with a few minor exceptions – the information is unrelentingly practical, and I admit that my training as an architect rears its head at times. One example: the section on page 103 where the authors rail against what they call “designer staircases.” I do love a dramatic stairway.

You can download the Table of Contents and the “Two Hundred Snappy Rules” in PDF for free from the ALA Editions website. This is not an inexpensive book, but we are in the process of ordering two more copies to circulate for our professional collection. Contact Lauren Stara if you have any questions.

A Guide to Town Meetings

This is a guest post from Patrick Borezo, Director of the Goodwin Memorial Library in Hadley

In November of 2017 voters in Hadley, Massachusetts let their voices be heard at the ballot box. Hadley had made the historic decision to accept nearly four million dollars from the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners and to allocate the balance of funds needed to construct a new library. The Goodwin Memorial Library, constructed in 1902, would be replaced with a single story, fully accessible facility with greatly improved parking, collection capacity, and meeting space.

Hadley is a community of roughly 5,250 people with a town meeting form of government. Because town meetings are attended by a minority of residents the committee felt that it needed to mobilize between 300 and 500 supporters to deliver the needed two-thirds majority. This would be especially important in case of an organized opposition. The Committee’s Get Out the Vote strategy for both the special town meeting and ballot vote emphasized one-to-one communication between neighbors, particularly those who were likely to support the library. The use of attendance lists from previous Town Meetings was crucial in this process as it identified those who were already likely to attend based on previous behavior. GOTV volunteers attended brief strategy meetings and were each asked to contact ten to twenty residents who were seen as likely to support the library project. Volunteers asked each person contacted whether they would likely attend the special town meeting on the specified date and if the answer was affirmative they were also asked how many others from their household were likely to attend. This effort worked as a running head count, but also as a way to gently remind likely supporters of the town meeting and its relevance to the library project if they were not already aware.

Additional efforts included a number of supportive letters to the editor of the local newspaper as well as several press releases that resulted in media coverage of the special town meeting. A small run of lawn signs (underwritten by the Friends of the Library) was distributed to the homes of supporters in the week leading up to special town meeting.

The special Town Meeting held on August 29th was attended by nearly 500 residents putting the hall at full capacity. Some twenty to thirty people participated from the hallway which was used for overflow from the main room. Roughly a dozen members of the public spoke articulately and passionately in support of the article from the floor. The final vote was 449 in favor with 28 opposed. The nearly unanimous sea of hands held up to vote “yes” was a powerful affirmation of the importance of the library and the services that it provides to this community.

The successful result at Special Town Meeting sent the borrowing question to a town-wide ballot on November 14, 2017. The strategy for the vote was similar to the lead-up to Town Meeting, with the majority of effort going to reactivating those in attendance in August. Additionally, a town-wide mailing was undertaken and paid for by the Friends of the Library. These postcards were mailed to every active postal address in town, rather than targeting supporters only. As in August, lawn signs were created with the slogan “Our Community, Our Library”.

Again, the operative assumption was that participation in the ballot vote would represent a minority of Hadley’s total population. To succeed at the ballot a simple majority is needed rather than two-thirds majority. Ultimately 1,157 votes were cast. 683 in favor and 470 opposed (with four left blank).

Looking back over a process that began in earnest in the Spring of 2014 when Hadley accepted the MBLC’s Planning & Design Grant I have taken several lessons from our journey so far. Most of these may seem like common sense, but I think they are all worth repeating.

- Know your community, but don’t buy into all of its conventional wisdom.

We have all heard from community members who, claiming to know it very well, believe that it can never change. This is especially true when there are memorable instances from the past where a divisive issue led to a bitter defeat for an important project. Every campaign happens in its own context. In being offered something worth the effort and risk each community has the opportunity to follow a new direction and write a new chapter. And who knows, perhaps the community that we thought we knew so well has changed a bit more than we anticipated.

- Say, “Yes” as often as it is possible and practical to do so.

The early stages of planning are a great time to paint with a broad brush and think big. An important part of building consensus is to hear from the community about what they think should be included in such a transformative project. I was often surprised by how important the functional aspects of the proposed library were to residents who engaged with the planning process. Would we have a green building? Can the Children’s Room be situated so as to contain noise and maximize safety? What about accessing the meeting rooms after hours? These kinds of questions arose far more than those relating to the appearance of the building, for instance. People could see the possibilities in the new library and asked us to consider many suggestions, some more practical than others. As often as we could we said “Yes” in terms of at least considering any idea brought to us. Some of these ideas might not make it into the final plan, but all ideas were considered important enough to merit consideration. And if that “Yes” must ultimately become a “No” there would be a solid rationale to back up the decision.

- Build consensus through transparency.

It is amazing what you can learn about yourself or the things you are working on “through the grapevine”. Scuttlebutt is a natural and unavoidable aspect of anything political. Decisions made out in the open will be questioned rigorously, fairly or unfairly, but when the perception is that important decision-making is being made behind closed doors then trouble is sure to follow. A savvy opponent will use any procedural mistakes made by a committee to undermine public confidence and slow down the process. Always follow open meeting law and advertise meetings as widely as possible. Provide information as quickly and completely as possible, even when it is to someone working against your project, as is your obligation. At the end of the day it’s the integrity of the process that matters and those in the community who are objectively on the fence may well be swayed by that integrity to help write a new chapter.

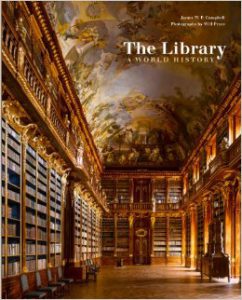

A Little History Lesson

By Lauren Stara, MBLC Library Building Specialist

The Library: a World History came out a few years ago and I did a blog post to the short-lived MBLC Construction Blog in January of 2014. I wanted to share it here because it was such a great read.

The book was written by James W.P. Campbell, with photographs by Will Pryce. I saw the review and it sounded interesting, but to be honest I thought I’d ooh and aah over the photos and put it on the shelf.

Au contraire. I started reading the introduction and I realized that this was not just a doorstop with pretty pictures. I’m about half-way through and I have learned about form and design in the library building type from ancient Sumer to the late nineteenth century. I’ve gleaned some great cocktail party conversation starters. For example, did you know that most of the knowledge we have about the earliest libraries is because of fire? Clay tablets, usually just baked in the sun, were “fired” when their building burned. These hardened tablets are the ones that have survived, in contrast to the total destruction of papyrus, vellum and paper in fires. Later libraries were entirely lit by daylight until the advent of electricity, since the potential destruction by lamps or torches was so great.

As the format and production of books evolved, so did the spaces and shelving styles that house them: from lecterns to alcoves to perimeter shelving; from chained books to grillwork cabinets to open shelves. We think we have it bad now, with collections growing out of the available space – imagine the poor librarians right after the printing press was invented! Collections, literacy rates and the services required grew exponentially.

The 21st century is the first time since Gutenberg that the shape of libraries has been determined by something other than printed books. People are using public libraries in unprecedented numbers. They want access to collections, sure, but they also want internet via library stations and wi-fi, programs and activities, and just a place to hang out. Libraries have become the de facto community center in many places, and people take up more space than books do.

We’re in a period of great flux now, and it’s harder than ever to answer the question “what will libraries be like in 20 years?” Over the last several decades, librarians have proven to be masters of resilience and flexibility; our buildings must reflect that flexibility. Mobile technology, furniture and shelving with a welcoming atmosphere and a philosophy of service is the model that seems to be working. We have to be ready for anything.

Postscript: this fabulous quote from the book shows that some things never change:

“The results of Beaux-Arts planning were all too often libraries in which librarians worked in increasingly impractical layouts, designed to look good on plan rather than function well in reality. This was the tyranny of the symmetrical plan.” –p. 225

We have this book in the MBLC professional collection, available through NOBLE or the Commonwealth Catalog.