Have a news story you’d like to share? Please email the link to MBLC Communications Specialist June Thammasnong (june.thammasnong@mass.gov), thank you!

🗞️Local News

📄MBLC Funds Statewide eContent – MBLC Press Release (8/7/2025)

At its August board meeting, the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners (MBLC) approved $500,000 in grants to Automated Networks to purchase eContent for the Library eBook and Audiobook (LEA) program. LEA gives Massachusetts residents access to eBooks, audiobooks, and more from 400 participating libraries from across the Commonwealth. This statewide system allows eContent to be shared in a similar way to physical materials, opening up access that was previously unavailable for eBooks and audiobooks. The LEA collection has grown 37% over the past three years and totals almost 1.5 million eBooks and Audiobooks.

📄New library at 38 Avenue A in Turner Falls preferred over Carnegie Renovation – by Erin-Leigh Hoffman, Greenfield Recorder (8/15/2025) – This project is part of the MBLC’s Massachusetts Public Library Construction Program-

TURNERS FALLS — The property that once housed a Cumberland Farms and was later eyed for a mixed-use development may be starting a new chapter, this time as a library.

📄 Masters of their craft: Elizabeth Taber Library launches new makerspace – by Grace Ann Natanawan, Sippican Week (8/19/2025) – Elizabeth Tabor Library in Marion received an LSTA Creative Communities grant in 2024 to help support this project –

LUNENBURG — The Boston Bruins have teamed up with libraries across the state to encourage children and teens to keep reading over the summer.

The Lunenburg Public Library and the Thayer Memorial Library are two of just 12 public libraries selected to receive a special summer reading visit from Bruins’ mascot Blades.

📄Where will Yarmouth build a new, modern library? Here are 5 possible sites. – by Susan Vaughn, Cape Cod Times (8/21/2025) – This project is part of the MBLC’s Massachusetts Public Library Construction Program –

South Yarmouth and West Yarmouth libraries are too small to serve the town, library officials say. Now, a new building is planned for both.

📝 The Future is Unknowable, but the Past Can Help Us Prepare – by Al Hayden, MBLC Blog (8/25/2025)

Welcome back to another edition of Fortifying Your Library! While I remain committed to being a policy nerd and will continue to offer policy-based content that hopefully helps your libraries, there are other ways to fortify your library. I wanted to spend some time addressing a question that has been on my mind: what happens to public libraries during an economic recession? As you may suspect, what prompted this inquiry was the large quantity of media speculation as to whether or not the US is heading towards a recession.

📄Letter to the Editor: Funding Cuts and the Revere Public Library – by The Revere Public Library Board of Trustees, Revere Journal (8/21/2025)

Many of you may not realize that your public library is funded in several ways: through the City of Revere budget, the Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners (MBLC), and the federal Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). IMLS was recently defunded by Presidential Executive Order #14238 and this letter is about the impact on your public library of the loss of this agency and the funding it administered.

📄 Bruins Mascot to Celebrate Summer Reading at Local Libraries – by Cheryl A. Cuddahy, Sentinel & Enterprise (8/3/2025)

LUNENBURG — The Boston Bruins have teamed up with libraries across the state to encourage children and teens to keep reading over the summer.

The Lunenburg Public Library and the Thayer Memorial Library are two of just 12 public libraries selected to receive a special summer reading visit from Bruins’ mascot Blades.

📺 Bruins Mascot visits Wilks Library– by New Bedford Government Access (8/19/2025)

NEW BEDFORD — Boston Bruins mascot Blades visited the Wilks Library in New Bedford! New Bedford Cable Network captured all the fun here:

🗞️ National News

📄 How Libraries Became ‘First Responders’ for America’s Opportunity Gap – by Wilfred Chan, Carnegie Corporation of New York (8/25/2025)

Last year, the New York Public Library’s English classes were attended 200,000 times — and it still can’t keep up with demand.

📄 Attorneys General Beseech R.I. Judge to Protect IMLS – by Nathalie op de Beek, Publishers Weekly (8/25/2025)

As the calendar ticks toward September 30 and the end of fiscal 2025, at which time U.S. legislators will determine FY 2026 appropriations for public institutions, 21 states’ attorneys general have asked the U.S. District Court of Rhode Island to enter a summary judgment in State of Rhode Island v. Trump. They seek a permanent injunction to keep the Institute of Museum and Library Services, along with the Minority Business Development Agency and Federal Conciliation and Remediation Service, fully staffed and operational.

📄 More Details Emerge About IMLS Dismantling; Plaintiffs in RHODE ISLAND Lawsuit Seek Permanent Injunction – by Kelly Jensen, Book Riot (8/26/2025)

More details emerge in what happened during the IMLS takeover by DOGE and what might happen in the federal lawsuits against the agency’s dismantling.

📄 New ULC Analysis Shows Downtown Libraries Are the Anchors Cities Need – Urban Libraries Council (ULC) (8/27/2025)

Office attendance has yet to rebound, but central libraries are bringing people and energy back to city centers, as our new data shows–

Public libraries have long been at the heart of American cities, and the large central libraries that serve as the flagship of most systems are among our most vibrant public spaces. Whether historic architectural landmarks or modern works of art, they collectively represent over 215 million square feet and serve nearly a third of the U.S. population – the indoor public space of America, where all offerings are free of charge.

View ULC’s new data and visualization based on analysis above

📄 Braille libraries offer community. What happens when funding cuts close them? – by Hannah Goeke, Christian Science Monitor (7/31/2025) – Includes an interview with Perkins Library Executive Director Kim Charlson-

Marci Carpenter reconnected with her love of reading through her fingertips. When her vision became more limited, learning braille gave her a new way to experience the world. She still remembers how the words of Robert Frost’s poems came alive again through soft bumps embossed on thick paper.

But it was the Washington Talking Book & Braille Library in Seattle that gave her a place to connect.

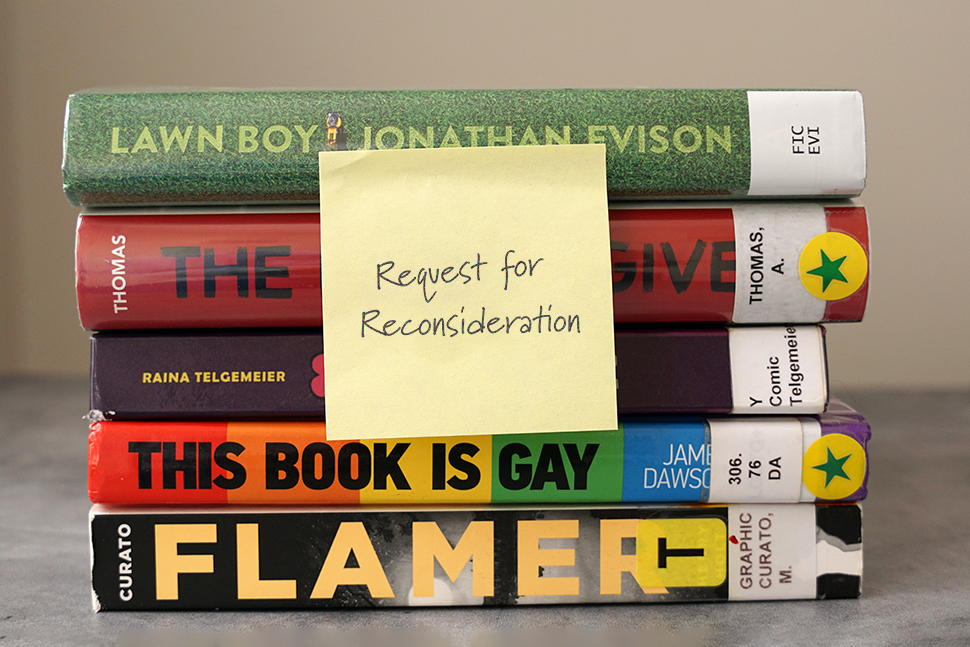

📄More and more books are being banned. SoCal libraries find a solution – by Annie Goodykoontz, Los Angeles Times (8/14/2025)

To combat book censorship, some Southern California public libraries, including Los Angeles, Long Beach and San Diego, are joining libraries nationwide to provide access to online library cards. Children as young as 13 can get a free e-card to access the libraries’ catalog of e-books and audiobooks, without parental permission and without any challenges they may face to get a book in their local library.

📄 PLA celebrates Project Outcome success; transitions resources for free ongoing use – by American Library Association (ALA) Press Release (8/19/2025)

CHICAGO—The Public Library Association (PLA) today launched a suite of outcome measurement resources developed as part of the Project Outcome toolkit. The new webpages culminate a decade of work dedicated to sharing the impact of public library services and programs via simple surveys and an easy process to measure and analyze patron outcomes. The “Utilizing Outcome Measurement to Improve Library Services” webinar on August 28 will guide participants through the templates and tools.

📄 At airport libraries, books fly off the shelves – by Hannah Simpson, The Washington Post (8/18/2025)

Airports all over the country have introduced book exchanges, to the delight of literary travelers.

📄 Library of Congress acquires only known lyrics sketch of ‘Over the Rainbow’ – Chloe Veltman, NPR (8/25/2025)

The Library of Congress has acquired rare artifacts related to the beloved 1939 film The Wizard of Oz.

The treasures include 35 musical manuscripts from composer Harold Arlen and lyricist E. Y. “Yip” Harburg’s creative output, including the first handwritten drafts of music and lyrics from some of the most well-known The Wizard of Oz songs, draft song lists and correspondence from the director of the film, Mervyn LeRoy.

Among the artifacts is the only lyric sketch for “Over the Rainbow” known to exist.

Related: 📄Want to See the Original Lyrics for ‘Over the Rainbow’? All You Need is a Library Card – Ella Feldman, Smithsonian Magazine (8/27/2025). Link to full article from Smithsonian Magazine

📄 How Portlanders have expanded Little Free Library’s ‘take a back, leave a book’ – by Crystal Ligori, NPR (8/23/2025)

In Portland, Ore., people have gone beyond the trend of Little Free Libraries, creating all kinds of sidewalk installations to spark joy.

o*Links provided to external (non-MBLC) news stories are done so as a convenience and for informational purposes only; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by the MBLC. MBLC bears no responsibility for the accuracy, legality, or content of the external site or for that of subsequent links. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content.