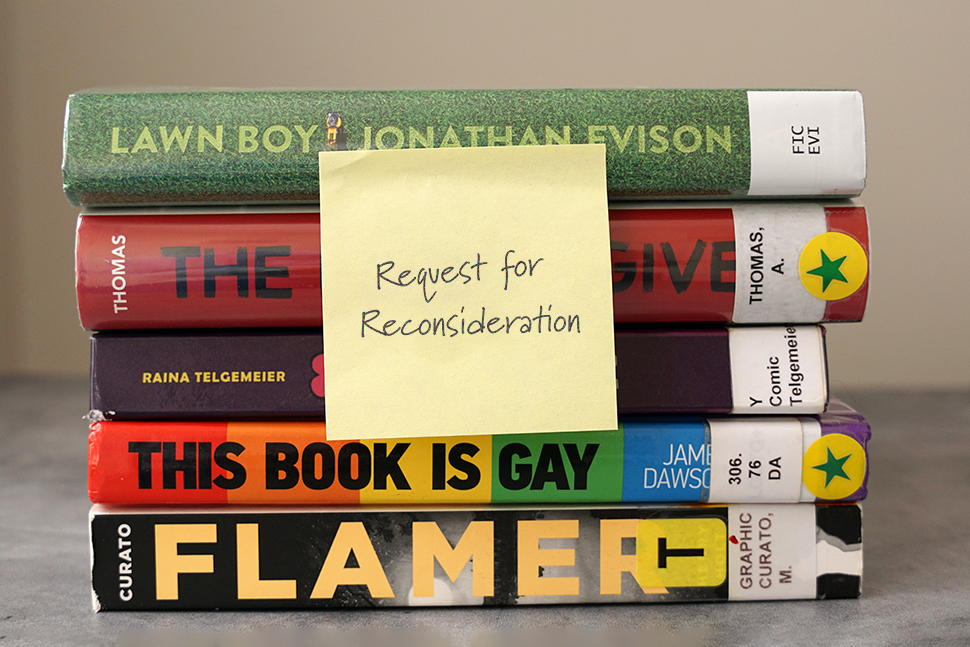

If you are already looking over your collection development policies based on our last blog post, here is the other, crucial side of your collection development policy: offering a space for patrons to express their concern about library materials, or a Request for Reconsideration.

You may have noticed how much the word “professional” was used in the last post. That is because, while librarians are trained professionals, they are often not recognized as such. It’s not common knowledge that to be a professional Librarian, someone needs to hold a Master’s in Library and Information Science (MLIS). Because we deal so frequently at the intersection of information and people, the rights upheld by the First Amendment come into play more often than many people would expect and it’s essential that the professional, non-partisan nature of librarianship should be emphasized.

What is a Request for Reconsideration?

When it is presented in good faith, a Request for Reconsideration (RfR) opens discourse between the library and its community and can create a better understanding between both parties. It’s important for the public to understand, however, that RfRs take extensive time and effort which ends up costing the library and the municipality’s taxpayer dollars – time, effort and taxpayer dollars that are taken away from doing another part of library work for your community. To allow professional librarians to continue to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars and to understand the basis of a good faith request, requests for reconsideration should require the patron to fully consider their objection and put it in their own words. When putting together a standard RfR form to accompany your collection development policy, consider beginning with a basic template (you can find an example here) and then adding the following requirements to the process in order to protect the time and efforts of library staff and encourage good faith challenges:

- A signature that acknowledges both receipt and understanding of the collection development policy, including the review process

- A notice that challenged materials will NOT be removed, relocated, or restricted from any collection while under consideration

- The length of time before a specific title (item, material, etc.) may be challenged again once a decision has been made (for example: once a determination has been made a title cannot be challenged again for 2 years, including new editions that may come out)

- Notice that only an official reconsideration form will activate a reconsideration procedure. * Phone calls, rumors, voiced concerns, emails, social media comments, etc. are not sufficient to initiate a reconsideration process, though it is important for the library to keep track of these “informal” complaints. Anyone bringing a concern to the library may (and should) be given an official reconsideration form.

- Notice that an official reconsideration form must be filled out in its entirety. Incomplete, anonymous, or otherwise partially completed forms will not be sufficient to activate the process

- Notice that form(s) must be filled out in the challenger’s own words; copied and pasted text from other sources (websites, social media, etc.) invalidate the personal nature of the concern and may not be considered

- A statement requiring that the person raising a concern be a member of the community (ex. resident, cardholder, etc.). For example: “In striving to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars, challenges brought by those outside the library’s community may not be considered”

- A request that the patron suggests alternative material that is of equal literary quality, can provide similar information, and convey as valuable a picture and perspective of the subject as the item they are requesting be removed

- A description of the appeals process should the patron disagree with the library’s initial response to the reconsideration request

- Ideally (depending upon library staffing levels), the process should consist of a review by a committee of professional staff appointed by the director

- 1st appeal of the committee decision should be to the Library Director

- 2nd (and final) appeal lies with the Library Board of Trustees who will conduct a challenge hearing and render their binding decision at the following Board meeting.

Handling challenges to library materials

Should a patron want to challenge library materials, they should be made aware of what to expect on the library’s part as well. Describing the process that a request for reconsideration will go through provides the community with transparency and accountability on behalf of the library.

- The Library should strive for a review timeline that is reasonable based on staffing conditions, ** but should also be timely in relation to a filed complaint. Two weeks to 1 month for a full, formal review from the filing of the initial complaint to providing the complainant with a decision is generally reasonable. Unless a severe staff shortage prevents the process from moving forward, all efforts should be made to keep the review process moving along swiftly.

- The Library should consider the item in question in its entirety, not taking passages, excerpts, clips, or descriptions out of context

- The Library should review all parts of the purchasing process and review the decision to make the purchase in the context of the collection development policy

- The Library should remain as objective as possible. Should the challenged item not meet the selection criteria, the library must be willing to acknowledge that the item is unsuitable for the library collection and withdraw the item.

- Whenever possible, the person who made the initial selection to purchase the item should not be on the appointed committee to review an item when it is challenged.

Additional considerations you may want to make in regard to a reconsideration process:

- Require this process for challenges not just to selected materials, but to displays and programming as well. Displays and programs are also library services that are thoughtfully curated by professionals and are subject to internal guidelines and policies. You can include programming and displays in your collection development policy or have a separate policy on the curation and selection of display materials and programs. All complainants should receive a copy of the relevant polic(ies) to review, so make sure you are covered with what they may be objecting to.

- Keep frontline staff interactions at a minimum. Challenges are often highly charged exchanges, even when conducted civilly. This puts a stress on anyone receiving the complaint. Train frontline staff (use scripts if you can***) to acknowledge that the person is bringing a concern to them; inform the person that there is a formal procedure that all those who want to pursue a complaint must follow and; if at all possible, send that person to the Library Director (or official designee in the Director’s absence). Frontline staff’s efforts are best directed toward their regular duties, responding to the needs of patrons with more routine requests

Expressing the responsibilities of both the complainant and the library ensures that a good faith challenge receives full consideration; reduces the appearance of arbitrariness (both in responding to a challenge and selecting materials); and clarifies the duties of the library staff when this situation arrives at your library’s doorstep.

* The library should strongly consider funneling all informal RfRs through the library’s administrative team. This will both limit the amount of time desk staff spend listening to complaints that, ultimately, they won’t have the power to address; and allows the official RfR form to be given to the person with a concern by someone with the knowledge to fully answer questions about the collection development policy and authority to respond to the patron’s request.

** Staffing shortages are all too common in library services, particularly with professionals leaving library service. If you find at the beginning of the process that you are unable to follow the timeline set out in your policies, it is crucial that you are upfront about this, communicate it in an objective manner to the patron making a complaint and provide the patron with an updated timeline based on your current staffing situation.

*** More information on scripts will be coming in a future blog post!