Welcome back, and thank you for sticking with me! To explore how libraries behave during a recession, I’ve utilized metrics that align with the time frames in Mabe’s study, using data from the Annual Report Information Statistics (ARIS) submitted by libraries annually. Although ARIS has evolved over the years, the data available from 2006 onward allows us to make consistent year-to-year comparisons. While your library might have additional data, I’ve limited my analysis to data points that have remained consistent since 2006.

Basic Calculations

Let’s examine programming attendance—how many people attended library programs—before and during the Great Recession. For the years 2006, 2007, and 2008, the average program attendance was:

- 2006: 5,200

- 2007: 5,550

- 2008: 6,294

- Total: 17,044

- Average: 5,681

For 2009, 2010, and 2011, the figures were:

- 2009: 5,994

- 2010: 6,112

- 2011: 6,336

- Total: 18,442

- Average: 6,147

(I highly recommend putting any of your data into a spreadsheet and using the =SUM and =AVERAGE formulas to do the math for you.)** Right away, you can see that the data for both total attendance and state averages is higher during the recession. Massachusetts libraries saw, on average, 466 more people (6147-5681=466) attending programs each year when the economy was in a downturn.

Let’s see what the percentage change across that time period is. To calculate that number, you can use this formula: Percent change = (6147-5681)/5681. (There’s likely a spreadsheet formula to do this, but I didn’t find it. Feel free to let me know if you do!) We end up with a positive number 8.2% meaning that libraries saw 8.2% more people attending library programs than they did prior to the recession.

If we think about the basic implications of this information, it follows similar logic found in my previous posts. In an economic downturn, people are looking for ways to save money; they’re looking for options to help them get back into the job market; they want to refine skills to progress in their current positions or to start a new career; they’re trying to make more productive use of their time. The library can accommodate all of these needs through a variety of programming options, so it would make sense that communities take advantage of library programming more during a recession.

What About More Recently?

Let’s look at more recent averages for Massachusetts libraries:

- 2022: 1,434

- 2023: 7,733

- 2024: 9,436

- Total: 18,603

- Average: 6,201

This more recent data available provides some extremely interesting insights. First, let’s talk about the low number from 2022 and the elephant in the room- the pandemic. In FY22, which included 6 months of 2021, many libraries were barely open, let alone programming, so while this number in isolation is very low, it’s actually pretty impressive in context, especially given at least some of those programs were likely virtual which was new to everyone- including libraries.

Next, let’s take a look at those high numbers for 2023 and 2024: the lower of which is nearly 1,500 people higher than the highest number from the Great Recession, and the higher of which is 1700 people higher than the previous year. Without any potential extrapolation, these numbers are already telling us that library programming attendance has continued to increase beyond the recession, has rebounded in a big way after the pandemic, and is increasing year over year. So, while the 3-year average is only slightly higher than the Great Recession average (54 more people on average) the pandemic data is bringing that average way down. For the sake of curiosity, if we take the average of just 2023 and 2024, we get 8,585 people, an average increase of 2,438 people attending library programs over the Great Recession data.

Time to Project

Now let’s add extrapolation into the mix. To estimate what your programming attendance might look like in the event of a future downturn, take the average of your most current three years, multiply it by the percentage difference between pre- and Great Recession averages and add that number to your current 3-year average. For libraries across MA, that looks like:

(6201*.082) + 6201 = 6710.

This means the estimated average for program attendance in libraries across MA would increase by 509 people creating a total average of 6,710 people attending programs annually.

Given the outlier of the pandemic year, I think in this particular case,*** it would be worthwhile to calculate an approximate low-end and high-end estimate, as long as it is very clear which numbers we are using. So, if we consider an 8.2% increase for higher average program attendance of 8,585, there could be a potential increase in program attendance of 704 people, putting the total potential average program attendance at 9,289.

Implications for Libraries

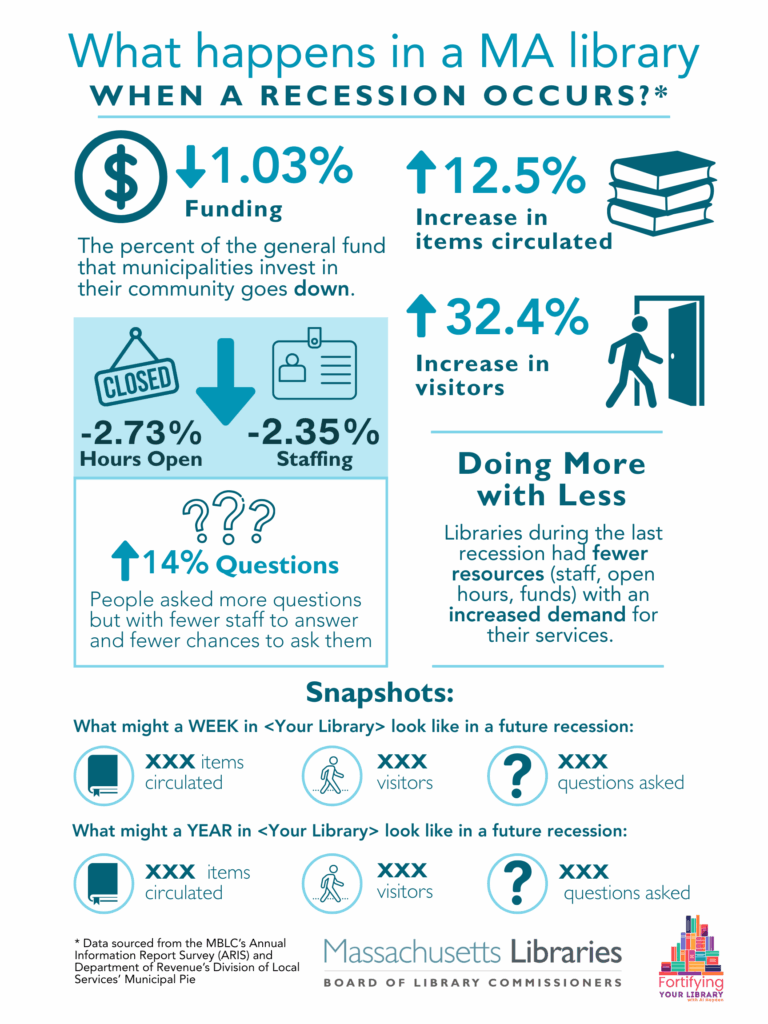

Let’s take a look in what those numbers could mean for libraries in the event of a future economic downturn. The basics remain essentially the same as they did in my previous posts in this series. Libraries will face having to do more with less. In this case, they will be shouldering more people attending programs. Whether they are seeing an increase in attendance for programs they are already running or if, as they often do, libraries rise to meet the needs of their communities and create additional, new programming that people attend, or some combination of the two, they will have less funds and fewer staff to accomplish this.

Invisible Work in Library Programming

Much like the summer reading statistics from my last post, this assessment doesn’t take the full picture of invisible work into account. Programming is often done at all staff levels (from part-time paraprofessionals to full-time, MLIS holding department heads and, occasionally, library administration), and any loss in staffing will essentially take away institutional and specialized knowledge that may not be so easily transferred to another staff member.****

Loss of a staff member often means loss of a program (or programs) and leaves the remaining staff scrambling to fill in the gap. Programming is also, and I cannot stress this enough, hard work. I know from experience. It is largely a labor of love born of passion, enthusiasm, and the unique intersection of community need and cultivated skill. I know very few programming librarians who are not revived by the creation of a new program or finding out they have (or have always wanted to learn, usually on their own time) a skill that can be beneficial to their community. But I also know very few programming librarians who are not routinely tired.^

What Library Programming Is

Library programming is a great deal more than what patrons see for the 40 min – 1 hour when they come for a lecture, discussion, cooking class, story time, resume building, crafting klatch, etc. Any program involving an outside speaker or performer requires negotiating dates (and often speaker fees), attending to the performer’s needs and preparing the venue for the speaker’s requests. There is the prepping beforehand of materials, samples, supplies, etc., many of which the programming library will have to acquire themselves, that will be used during many programs. There is the coordination among other librarians to ensure that the library’s spaces are not being scheduled for different programs at the same time. They will have to keep track of registrants, ensuring that fire codes and any outside programmer specifications have been followed. Much of this will all be undertaken months in advance because they will need to publicize the event, including the creation of flyers, social media posts, making sure front line staff are aware of the program, adding the event to library calendars, etc. And since many libraries do not have a line item dedicated to library programming, many library programming staff will be tasked with figuring out how to pay for a program, whether this involved requesting donations, making an entreaty from the library’s Friends or Foundation, applying for a grant, or getting creative with the supplies the library already has on-hand.^^

The above paragraph describes the effort that goes into just the preparation for one library program. Now consider that most library staff members who program, run several programs at a time, mixing weekly programs with monthly programs with special events, and must keep track of all of those programs and run through the paragraph of abbreviated considerations I just listed out for each one of them while also going through their own specialized checklist depending on the particular needs of the programs they are running. I’ll spare you the redux of what staff need to attend to during and after a program. Library staff members who program are often a combination of event planners, contract negotiators, grant writers, performers, marketers, graphic designers and party hosts – and that is just for their programming duties. Many programming staff may also be front-line library workers, managers, catalogers and otherwise hold different roles within their regular duties.

An increase of 8.2%, which is a smaller percentage increase than most of what we’ve looked at in these posts, amounting to about 509 people attending programs over the course of a year may seem less significant than some of those larger percentages I’ve discussed before. But taken in context with the invisible work that goes into programming and the likelihood that libraries will be taking on these additional attendees with fewer staff, fewer funds, and fewer hours open, thereby condensing the amount of people, the broader picture becomes one of an overstretched staff struggling to meet their community’s increased needs with fewer resources with which to do that.

*Refer back to my first post for a refresh on what those years were.

** Fun fact: if you take the average of all 6 years and if you take the average of the 2 averages for each 3-year block you get the exact same number. I wasted my time checking on that so you don’t have to!

*** The reason I’m making the exception for this particular data set is because the extremely low number for 2022 is not mirrored in the other statistics I talked about in my previous posts. On balance, for all of the other data points that I considered, the 2022 numbers were reasonably close to the 2023 and 2024 numbers; they were not so glaringly different when compared to the 2 later years as they are for programming and therefore did not have the same adverse impact for the 3-year average.

**** You may be surprised to find out just how much specialized knowledge is involved in running a baby story time or that not every personality type is well-suited to offering technology help sessions.

^ To be fair, I know few library workers in general who are not routinely tired, but for now, I’ll stay focused on the subject matter at hand.

^^ Hence, why so many crafts, especially in children’s departments, involve toilet paper rolls.

~ Al Hayden, MBLC Library Advisory Specialist